What do we actually want the future of transportation to look like?_

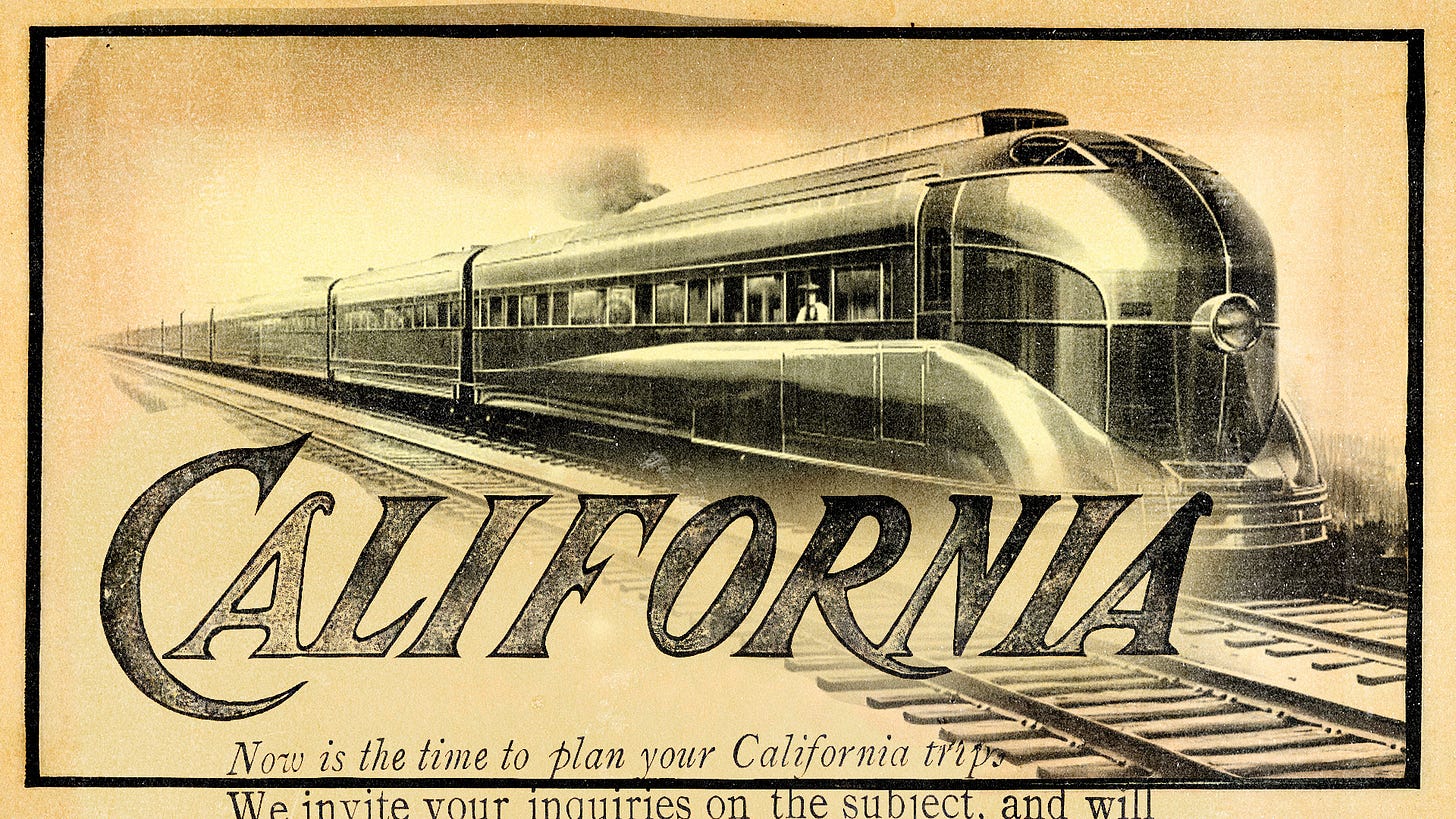

For California, the answer was high-speed rail—a bold promise to reimagine how we move across the state.

But fifteen years later, that future still hasn’t arrived.

The only part under construction is the [Merced to Bakersfield segment](https://hsr.ca.gov/high-speed-rail-in-california/central-valley/), a $36.7 billion project unlikely to open before 2032.

So why can Japan and China build thousands of miles of bullet trains… but California can’t finish one line? And even more uncomfortable: is building a high-speed train actually a good idea, once you run the numbers?

To answer that, we talked to some of the people who’ve tried to build this stuff—and who, despite disagreeing on the California project, both love trains.

But first! _A word from our sponsor:_

> Building the future takes people willing to take big bets on long timelines. [E1 ventures](https://e1.vc/) backs founders pushing the edge of what’s possible in science and technology.

>

> If you’re building something ambitious and looking for investors aligned with your vision, reach out to E1 Ventures.

>

### **Where Trains Actually Make Sense**

Let’s start with the basics: **where do trains actually work?**

In 2024, Amtrak reported record ridership—over **32 million passengers**, the highest in its history. Intercity and long-distance trains are quietly growing, not shrinking.

> I recognize it might look like we’re a competitor to high-speed rail. I’m pro high-speed rail. I would really love to see this happen, but we need to be able to do it in a way that makes sense. It’s sustainable. And frankly, that it’s a good use of taxpayer dollars. And I do think you can make the justification that, this is something worth investing in that we all benefit from.

>

> _Joshua_

We spoke with [Joshua Dominic](https://x.com/JoshuaKDominic), founder of [Dreamstar Lines](https://www.dreamstarlines.com/) — a company trying to rebuild passenger rail in America and prove that getting from SF to LA can be fast, clean, and actually pleasant.

> I tend to view transportation as a full system. You need to look at everything and really, really big picture out where it obviously makes sense, where it could make sense, and where it doesn’t make sense.

>

> Trains are really, really good in a particular segment, roughly 100 to 1,000 miles. Generally speaking, anything under a mile, people like walk or bike. Under 10 miles, rickshaws and tuk-tuks are really great. The U.S. we actually do have a version of this. but nobody thinks about it and it’s golf carts. After that, you have like traditional automobiles, which are really solid choice up till about a hundred miles. People don’t like sitting in cars for very long. At hundred miles, you’re looking at roughly an hour, two hours, where most people don’t mind sticking in a car for about two hours. But when you get to that two to three point, it’s a pain in the butt. And that’s where trains start becoming super compelling because you can get up, walk around. You don’t have to stop to go to the bathroom. And about 1,000 miles, it’s always gonna be an airplane.

>

> _Joshua_

Globally, that 100- to 1,000-mile window is exactly where high-speed rail dominates. Tokyo to Osaka—about **500 kilometers**—takes just **under two and a half hours** on the Tokaido Shinkansen. And Beijing to Shanghai—**1,300 kilometers** apart—connects in **four to six hours** on China’s flagship high-speed line.

San Francisco to Los Angeles is around **380 miles**—squarely in that window. On paper, this is exactly the kind of corridor where trains beat both cars and planes on the total trip experience.

But it’s not just about speed.

> So in terms of what people care about when they’re traveling, it comes down to really five factors. So the first one is going to be price. How much does it cost me to get from point A to point B? The second one is going to be comfortable comfort. The third is scheduling, like convenience. Then the other ones are environmental impact. These are kind of the different factors that people really optimize on when they’re thinking about how am going to get from point A to point B? And it turns out on the kind of 100 to 1000 corridor, trains can be the best across all of those.

>

> _Joshua_

By every quantitative metric—distance, demand, congestion, emissions impact—the SF–LA corridor is one of the most compelling high-speed rail opportunities in the United States. It’s short enough to beat a plane gate-to-gate, long enough to beat a car, and connects two megaregions that generate millions of annual trips.

Which makes the next part more painful: **why this particular project is so broken.**

### **California, by the Numbers**

Back in 2008, [California’s business plan estimated](https://hsr.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/docs/about/business_plans/BPlan_2008_FullRpt.pdf) the Los Angeles–to–San Francisco backbone would cost about $33 billion in 2008 dollars.

[Voters then approved $9.95 billion](https://www.hoover.org/research/californias-high-speed-rail-was-fantasy-its-inception) in state bonds, with a target of finishing the system around 2020. Fast-forward to today, and [the projected cost for Phase 1](https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/california-high-speed-rail-project-013503450.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAALmfamztGziSb2ppOo6Ik6c52OoCyfcUB8zMI4dCVkdvxm2P_3owg5lwbznOA_zsKV5arRLo7Z8_GdfYgg36E9NFR2NiZjIGTDmMa7Kj2MM8xon8UJ5gYefSZOQ8Q-CK4tDyOhumWM9qyOUR3pReCDHywxLggt05OaLf0BS5O859) has exploded to somewhere between $89 and $128 billion.

Meanwhile, the only segment actually under construction is the stretch from Merced to Bakersfield—about 171 miles in the Central Valley.

That piece alone is now priced at roughly $36.7 to $36.8 billion. More than the entire original budget for the full San Francisco–to–Los Angeles line… just for this single section.

That’s roughly **$200 million per mile**, in arguably the _easiest_ geography of the route possible.

For comparison, Brightline West—the private high-speed line from the LA area to Las Vegas—began with a cost estimate of $12 to $16 billion for 218 miles, and has since grown to about $21.5 billion, or roughly $100 million per mile.

And China’s national high-speed network—now around 30,000 miles of track—cost hundreds of billions to build, but on a per-mile basis typically comes in at a fraction of California’s cost, especially on flat terrain like the Central Valley.

And the Merced–Bakersfield line, by the Authority’s own projections, could **lose about $3.8 billion over 40 years of operation**.

So where does all that cost and delay come from?

> Why is it so hard in the first place? So I’m of the view that we’ve institutionally just, we don’t know how to do big projects. The regulatory environment has made the approval process so expensive, that it it’s really easy to get marred down, for people who are against those projects and want to hold them back. They have so many tools in their arsenal to just say, hey, look, we’re gonna make this more expensive.

>

> _Joshua_

> Part of the reason the high speed rail project is costing tens of billions of dollars is that they have like, completely separate, distinct, like conglomerates of contractors doing every single infrastructure crossing. It’s not just like, you know, the electrical contractor and the plumbing contractor and the digging contractor and so on, like five or six different companies getting together and doing like a batch like 10 miles at a time or the entire project, right? It’s like every single time the road crosses is a separate consortium.

>

> _Casey_

[Environmental review](https://hsr.ca.gov/2025/12/05/news-release-california-high-speed-rail-authority-releases-draft-environmental-document-for-los-angeles-to-anaheim-section/?fbclid=PAZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAc3J0YwZhcHBfaWQPMTI0MDI0NTc0Mjg3NDE0AAGnPszjYUjxV20vAUvKPpUt52Jl0u3hH7d2ftZwh60J7PKf7TPXBIiuTiXSKtk_aem_gdLT8UIaKmZqOGt4K3hhIA) for the project started nearly two decades ago. By 2025, about **463 miles** from San Francisco to Los Angeles/Anaheim had completed environmental clearance—but at the cost of **years** of delay and hundreds of millions of dollars in studies, hearings, and litigation.

And even if you fixed all of that tomorrow, there’s a second, nastier constraint you can’t vote away: **California’s geography.**

## **Physics vs. Geology**

High-speed rail at **200+ mph** is not just “faster trains.” It’s a geometry and materials problem.

At 220 mph, comfortable horizontal curve radii (pronunciation) are on the order of **6–10 kilometers**. Grades generally need to stay below a few percent over long distances. That means: You either slow way down… or you straighten the line with **tunnels and viaducts**.

California’s chosen route detours through **Tehachapi (pronounce) Pass, Palmdale, and Lancaster**, partly to find an alignment that can even _theoretically_ support high-speed geometry between the Bay Area and LA.

Even if this segment were solved tomorrow, it would likely cut only about twenty minutes off a trip that still takes around six hours.

That’s where former NASA engineer and ex-Hyperloop staffer **[Casey Handmer](https://www.linkedin.com/in/casey-handmer-60183262/)** gets nervous.

> So it is probably physically possible to build like a vacuum tube between Los Angeles and San Francisco and to put some high speed Megalov system in it. And these ideas have been actually kind of experimented with for more than a hundred years, if you really go into the archives. And I’ve worked at Hyperloop for two and a half years on a system to do this. But even if you had like just the world’s best technical managers working on it, giving carte blanche to acquire land where they saw fit and the local cities had to cooperate.

>

> Even if you deleted all that, even if I granted you that we pass some law that says that California high speed rail can just build as though it’s completely empty land without any regulations or whatever that slows everything down in California, it would still be a bad idea because California has mountains. Like really big mountains. Los Angeles is surrounded by them and San Francisco is surrounded by them and driving high-speed trains through them will either add hours to your journey going up and down or you’ll have to dig a tunnel that’ll cost a trillion dollars to build.

>

> _Casey_

On the most challenging segment, **Palmdale to Burbank**, early estimates put the cost north of **$20 billion** for just a few dozen miles—much of that in deep tunnels and tall viaducts. That’s well over **$500 million per mile** in one link.

And California is trying to do this in a country where major tunneling projects—like New York’s East Side Access—have hit **$1.5–2.5 billion per mile**.

So even under **best-case** institutional conditions, the physics and geology alone push you into trillion-dollar territory for a full statewide network.

But the way the California project is organized makes it even worse.

## **How the Project Itself Went Off the Rails**

While the physical obstacles are daunting, the bigger challenge may be the _way_ we build things: a tangle of rules, stakeholders, and planning assumptions that make it nearly impossible to start small and scale up.

> With Dreamstar, what we said is like, Hey, if I’m starting a railroad company from scratch today, how would I do it? And I went and said, it’s too expensive to build.

>

> Systems that were set up in 1975 and continue, arbitrary, the 70s, 80s have continued to percolate and that while set up with good intentions, fast forward to 2025, they’ve made it really difficult to get things done today. These policies were put in place with really good intentions, but they’ve outlived their usefulness because the world changed.

>

> When looking at future high speed projects, you need to figure out what’s the minimally viable product where it can prove out the demand is there, and then you can connect to it to create incremental service. I think that’s the way that the US needs to approach high speed rail.

>

> _Joshua_

Instead of an MVP spine between two mega-regions, California tried to build a **universal service map on day one**—with all the added bridges, interchanges, and politics that implies.

Layered on top of that is how the work itself is carved up.

> It’s absolutely insane. It’s beyond insane. It’s like everyone involved tried to figure out how to make it cost as much as possible.

>

> If you’re going that fast, it takes like 30 miles to turn a corner. you can’t go up and down over mountains. You have to go through them. You can’t build a suspension bridge that’s 10 miles long. So you have to build a tunnel that’s 10 miles long, deep underground, through the mountains in California, which are like generated by and destroyed by a harrowing series of infinite earthquakes. So like just the geology of California’s mountains that you have to now drill tunnels that cost more than a billion dollars a mile through. So horrendously complicated that it might just take a hundred years to finish the tunnel.

>

> _Casey_

The result is a project with **extreme per-mile costs**, even in some of the flattest and simplest terrain in the entire state.

The Central Valley segment is projected—by the state’s own modeling—to **lose billions of dollars over the coming decades**.

And the entire project has previously been under **federal review**, with Washington openly considering **clawing back up to $4 billion** in previously awarded grants.

So if the status quo is this broken… what are the alternatives?

### **Planes, Trains, and “Teleportation-by-Sleep”**

> I’m not saying it’s impossible for humanity to figure out how to engineer this tunnel, but like, why would you pour a trillion dollars worth of wealth that like California doesn’t have obviously into digging one tunnel between two cities?

>

> It’s just a really bad idea because it will cost like a thousand times more than just buying like a fleet of 737s that are owned and operated by the state of California and fly anyone who wants to go between any of the respective airports in those two cities for free.

>

> People say, if you talk about high speed trains as if like the maximum speed the Shinkansen ever reaches the speed you’re going to average between point to point. It’s not. You have to slow down for every damn station. takes 10 minutes to slow down and 10 minutes to speed up again. And you have to slow down anytime you go around a corner. Like the peak speed that Techevay reached one time on one specially aligned section of track is not the speed that your system will operate in general. And people don’t realize, but like high speed trains wear down the rails. Like really quickly, you have to re-grind the rails every six months. and have to replace them every three years, just from the friction of the steel wheel rolling over the steel rail. This is not a problem that aircraft face.

>

> Find an area that’s about a mile long, maybe two miles long put down a strip of concrete And and now anyone from any of the airports anywhere on earth of which there are 35,000. … What’s that? There’s an earthquake. Don’t care. Mountain? Don’t care. Someone accidentally drove a truck onto the grade crossing. Don’t care. Uh, farmers say they don’t want your high speed rail to cross their land. Doesn’t matter. You know, like it’s a long way. Like Los Angeles to San Francisco is what 300 something miles.

>

> _Casey_

The math is brutal. In difficult terrain, tunnel construction has run at approximately **US$1–2 billion per mile** or more in the U.S. Regular maintenance of high-speed rail tracks is far more intense than for aviation — for example, rail grinding is a recurring requirement whereas aircraft infrastructure avoids most of that wear. And the existing aviation network spans tens of thousands of airports globally, enabling marginal expansion of service at far lower incremental cost than carving new rail corridors across mountains.

But cost isn’t the only way to think about transportation. There’s a separate design space where rail can outperform aviation entirely: in turning a long trip into something comfortable, productive, or even enjoyable.

But that doesn’t mean rail is useless. It means we should be more **targeted** about the kind of rail we build.

That’s where Joshua’s approach comes back in—not as a 220-mph moonshot, but as something much more modest and arguably more realistic.

> And so what we’re doing with Dreamstars, you said, hey, look, given the frameworks today, what’s the best way to build a rail product that people will love and go, my gosh, this is wonderful.

>

> You’re basically teleporting. So you get on, you have an out, your evening time is a lot more flexible because what are you gonna do every day anyway? I’m gonna get ready for bed. I’m gonna brush my teeth. What am I doing every morning? I get up, I get dressed, I brush my teeth, I shave. And you can do that on our train.

>

> With Dreamstar, you can get a superior transportation experience of just like, hey, I got on, I sat, I did a little work, I went to the lounge car, I enjoyed a nice evening beverage or whatever, or I had a coffee in the morning. And all of that gunk that comes with today’s travel is gone.

>

> _Joshua_

Technically, this lives in a completely different design space. We’re talking about 79 to 110 miles per hour service on upgraded existing track, not 220-mile-per-hour trains blasting through billion-dollar tunnels.

It’s dramatically lower capital intensity because it’s delivered as a service layer on infrastructure we mostly already have.

And it doesn’t try to beat airplanes on raw speed. Instead, it competes on teleportation-by-sleep and on offering a total experience that feels better than flying.

A fast train between San Francisco and Los Angeles _could_ make sense. The distance is right. The ridership corridor is there. The tech is proven overseas.

But once you layer in U.S. tunneling costs and California’s mountain geology, a regulatory stack built in the ’70s and ’80s that has never been meaningfully redesigned, a route map that tries to serve everyone on day one AND a contracting model that turns every road crossing into its own mini-megaproject–

Suddenly, it becomes almost impossible to deliver.

That doesn’t mean we should give up on trains. Sci-fi gave us the dream of effortless, high-speed travel, a vision for what might be possible.

But the future we actually get depends on whether we can turn those visions into steel, concrete, and working systems in the real world. But the future of transportation will be defined by our ability to turn those stories into reality.

Around the world—Indonesia, India, China, Europe—countries are actually building high-speed rail at an astonishing scale. America can, too. We’ll keep following California’s project and every other effort across the country as this story evolves.

Until next time, keep on building the future!_

_–Jason_